When Céline Was There

Céline Sciamma’s films have often been defined by elegant naturalism, but there’s something more playful in her new one – fantastical yarns and magical realism pen a love letter to Japanese animation titans Studio Ghibli in Sciamma’s new tiny masterpiece. Steph Green connects the dots between Petite Maman, My Neighbor Totoro and When Marnie Was There.

In an early scene in Céline Sciamma’s Petite Maman, a little girl nibbles happily on a crisp. It’s impossibly cute and oddly moving, in a way both entirely inconsequential and crucial to understand who she is. Similarly, When Marnie Was There (which almost feels like it could be live-action, more so than most other Studio Ghibli films) makes space for tiny moments in a child’s life that other filmmakers may deem unimportant when dealing with magical realism. These stories pay dutiful attention to the inner worlds of sombre children, articulated through both the everyday and the fantastical. But as two films that could be in conversation with each other, they both individually examine how the past and present are in constant conversation, too.

When the diminutive, delicate Petite Maman premiered at the Berlin Film Festival earlier this year, several reviews delightedly name-checked Japanese animation titans Studio Ghibli as a visual and thematic influence. Seemingly a departure from Sciamma’s naturalism as a filmmaker, this fantasy deployed time-travel and doppelgängers to tell the story of a young girl coping with generational dislocation, understanding grief and learning the art of empathy. It’s a miraculous little gem that emanates gentle warmth and a fable-like feel: like many Studio Ghibli films, it’s a comfort blanket free of schmaltz.

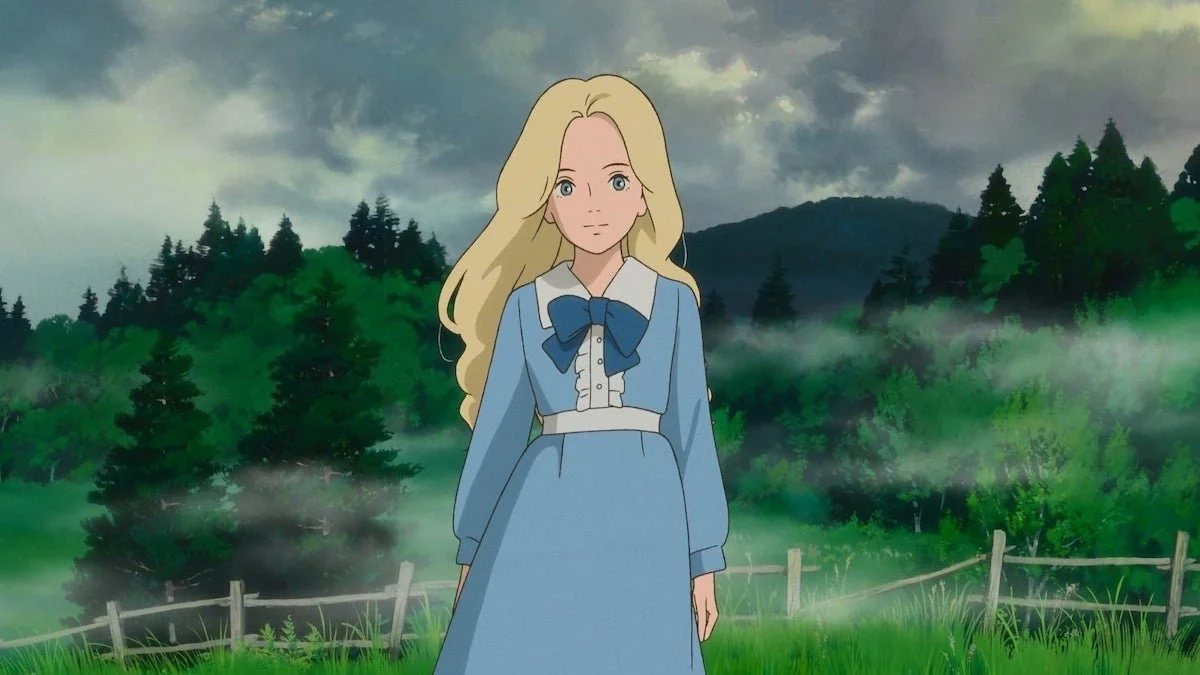

The films of Studio Ghibli have golden threads running between each disparate universe. Two such hallmarks are the presence of a female protagonist, and the way that they interact with the environment around them, with nature presented as a restorative force in the face of inner torment. “In this world,” protagonist Anna tells us near the beginning of When Marnie Was There, “there’s an inside, and an outside.”

A depressed and withdrawn 12-year-old who feels emotionally estranged from her adopted mother, she has been sent to stay with relatives near the seaside to help clear up a cough. This brief sojourn to an alien space is uncanny and unpleasant and first; it “smells like someone else’s home” and the beauty of the surroundings don’t tessellate with her inner struggles. Likewise, Petite Maman begins with eight-year-old Nelly temporarily moving into her late grandmother’s home to clear her things, before her mother mysteriously disappears. Nelly is left alone to work through her confusion and grief, in this space stuffed with the ghosts of her mother’s childhood.

Both Marnie director Hiromasa Yonebayashi and Sciamma understand how sometimes the slightest sensorial change can lift a dark cloud – be it long wet grass against bare legs, or the way a sun-dappled leaf glows in weak sunshine. Both Anna and Nelly dress in vivid textures, impossibly cosy in wool jumpers and dungarees. “The environments and relationships that surround people have a great impact on their psychological healing,” Yonebayashi has said. “This is why I chose to express the sensation we feel in the coldness of water, and in smell and taste.”

Probing past these hygge-friendly aesthetics, though, both filmmakers explore how externalising comfort can only go so far; it’s the people we meet in these locales that truly lift a mood. For Anna it’s the otherworldly Marnie, a blue-eyed and blonde-haired foreigner who helps her come out of her shell; for Nelly it’s her doppelgänger, a girl who calls herself Marion—the name of Nelly’s mother.

With a slight runtime and somewhat inconsequential plot, Petite Maman nods to My Neighbor Totoro. A Hayao Miyazaki classic and perhaps the Rosetta Stone to understand the worldview of Studio Ghibli, the film follows two young girls comforted by the mythical powers of nearby woodland in order to cope with the illness of their mother. Talking to Empire, Sciamma sang Miyazaki’s praises: “He takes children seriously, he takes female characters seriously. He has a serious connection to nature.” One of the first People Also Ask algorithmic options when you Google the film title is “What is the point of My Neighbor Totoro?”. There isn’t one, and that’s the simple beauty of it.

But simple stories can also possess depth. Studio Ghibli often floats between quiet fables and more complex, lengthy epics. They trust that children can keep up with and be moved by both. And it’s in this implicit trust of the emotional maturity of the (often) young viewer and protagonist that Sciamma and Ghibli share the strongest cinematic DNA. The majority of Sciamma’s features centre children or young teenagers – from Laure grappling with their gender identity in 2011’s Tomboy to Marie’s sexual awakening in 2007 debut Water Lilies. Similarly, the vast majority of Ghibli’s output focuses on young women and girls grappling with lofty ideas of identity, grief, and love.

When compared with the outdated gender politics of many Disney films, the studio’s common label as the Japanese Disney is reductive at best, insulting at worst. Some may argue that young children aren’t able to keep up with, or shouldn’t be exposed to, such mature themes. The films of Studio Ghibli and Sciamma make these kinds of arguments seem narrow-minded, an outdated view that belittles childrens’ capacities to appreciate and synthesise profound on-screen emotion.. After all, as Yonebayashi says, “Many children are tired and feel lonely.” In Petite Maman, this fact is echoed simply by Nelly as she nestles on the sofa with her grieving mother “I’m sad, too.”

When we’re young, our capacity for compassion is huge; we have so much space to give and receive love. “I’m already thinking about you,” young Marion whispers to Nelly. To Marnie, Anna says: “There’s so much I want to know about you, but I don’t want to find out too fast.” Children have a way of doing this: simple, passing comments are dropped into conversation and take the wind from your sails with their fleeting sweetness. Nelly ultimately learns that she is not responsible for her mother’s grief, nor should she lock herself away from it. And for Anna, it’s about learning that she isn't adrift in the world; both her absent biological family and real adoptive family love her deeply.

It takes a skilled, compassionate hand to organically weave natural emotions into magical worlds of fairytale forests and lake-encircled mansions. Like a painstakingly-made miniature, these stories reveal their craft upon closer inspection. Still, the message of Petite Maman, My Neighbour Totoro or When Marnie Was There couldn’t be more obvious, or beautiful: looking back to understand the past is the key to happiness in the future.

Steph Green is a freelance film critic and erotic thriller apologist from London. She writes for Little White Lies, the British Film Institute, Bright Wall/Dark Room, We Love Cinema and others.

Sign up to our mailing list and you’ll be sent our latest Storyboard post every week with The Friday Read. Mailing list subscribers are also automatically entered into our weekly competition to win one of five pairs of cinema tickets, so it’s truly a win-win scenario.